Two Box Structure, 1961.

Stainless steel,

165 3/4" x 53" x 27 1/2".

Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

It may not be possible to reach further as an artist than David Smith did, within and outside himself. The connections he made and the structures he devised to hold things together describe the limits of human comprehension, within a universe that is both reflected by and unconcerned with that comprehension. In Two Box Structure of 1961 the shapes couldn't be simpler, all stainless steel: two fairly large, flat rectangles, a smaller rectangular base, an even smaller circle at the top, and a number of long, mostly vertical linear elements connecting the other shapes in various ways. Standing on the ground, we are at the level of the horizontal rectangle, which has two legs (linear elements) supporting it. Another linear element extends far up from this rectangle and finally reaches the small circle some thirteen feet off the ground. This circle might be taken for a head, in the manner of Picasso's pin-headed Harlequin of 1915, connected to the body below, or perhaps the sun, also connected to the shapes below. Then the vertical rectangle could be another torso, supported by very long linear elements that bend like knees or elbows, so they appear to be oriented both upward and downward. There is some kind of "figure" here, and it is playing with our perceptions, particularly when we realize that the rectangles are like pictures that reflect light (when it is there), and absorb the surrounding colors into their steely surfaces. There are ways in which none of this may be pertinent. Two Box Structure is, after all, just a composition of shapes, but it is impossible to avoid associations and the extraordinary range of mind and emotion they suggest.

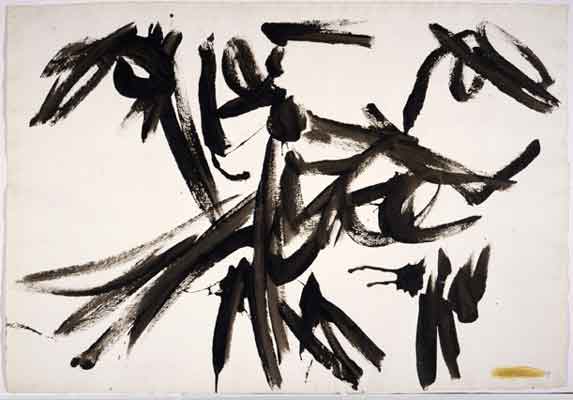

Before he began studying art in 1926, Smith had worked briefly on a car assembly line in Indiana (and he was later, in 1942-44, to work on a line assembling armored locomotives and tanks), so the idea of making something from parts was quite familiar to him. It was also not unlike the processes of Cubism and Constructivism that he was to learn about at the Art Students League in New York from 1927 through 1932. More immediately recent was the example of Surrealism, which might be said to represent a kind of Cubism or Constructivism of the inner self. Several drawings and a painting of the early 1930s derive his from trip with his first wife, the sculptor Dorothy Dehner, to St. Thomas, the Virgin Islands, in 1931-32. There is a convergence. The beach is already an assemblage--of shells, stones, shadows, figures, sea life, sky, water. It is also an ancient place, of the world and of the soul, where all these images are gathered. Nothing is specifically depicted in any of the drawings, but neither is anything, in its suggestiveness, inappropriate to the whole. As disparate as the images are, in shape, size, and character, they are all connected by lines that wind their way through the interior of the drawing and then, in different manifestations, encircles everything. In Untitled (Abstract Beach Scene), the shapes, and lines, are red, yellow, and white, the paper is blue, as though it were the sky or the sea.